“Blue-lining,” where banks stop lending in communities facing climate risk, could mimic the effects of redlining, a now-outlawed practice where lenders choked off credit to low-income, minority neighborhoods.

That was one of the many warnings about the economic risks of climate change to appear in a report published Thursday by the San Francisco branch of the Federal Reserve. It includes 19 papers by outside experts, a number of which focused on threats that climate change poses to the real estate market and vulnerable communities. The research also served up a variety of ideas for addressing those risks, ranging for market-focused fixes to more radical countermeasures.

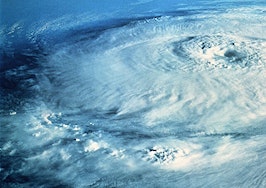

“Anyone who has seen the damage inflicted by flooding and storms in recent years will know that climate change is going to have a really, really huge impact on the real estate market, especially in low-lying coast areas, and especially in poorer, more low-income areas,” said Thomas Hanna, a political economist who authored one of the papers. “You have the prospect of areas that have been very disinvested and very disenfranchised being further cut off and further abandoned by capital and insurance.”

“Some central banks especially in Europe and Asia are very much further ahead of the U.S. when analyzing the risks of climate change,” he added. Nonetheless, he thinks the San Francisco Federal Reserve’s decision to issue the papers is “quite significant” and marks a “very important” indication that the “Fed is starting to take this crisis more seriously.”

One of the papers, authored by the former chairman of the Mortgage Bankers Association, Michael D. Berman, noted research has found that U.S. coastal properties facing sea level rises of 6 feet or more already sell for roughly 7 percent less than comparable properties at higher elevations.

And another cited research based on Zillow data concluded that climate change puts 10 percent or more of the housing stock of 175 communities at risk — 40 percent (67 communities) of which already have poverty levels about the national average.

Continued increases in sea levels, losses from weather events, avoidance by homebuyers and rising flood insurance rates “may adversely impact the tax base of municipalities at the time when more tax revenue is needed for flood mitigation infrastructure and other adaptation investments,” Berman wrote.

And without new countermeasures, climate-related risks could pose “a threat to the availability of the 30-year mortgage in various vulnerable and highly exposed areas.”

In effect, lenders, unwilling to accept the risk, could end up “blue-lining” certain areas, Berman wrote. The phrase is a reference to redlining, in which lenders avoid mortgage lending in neighborhoods with large proportions of people of color or poverty.

The 1968 Fair Housing Act and the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) were among laws that were passed to eliminate redlining, but research suggests redlining continues in less overt ways today.

Part of how the CRA combats redlining is by encouraging banks to make investments in low-income communities. One way to guard against blue-lining would be to task the CRA with doing the same for investments that prevent or mitigate climate-related damage, suggests a paper by Laurie Schoeman, the program director of a disaster recovery initiative with Enterprise Community Partners.

Another proposal, put forward by Berman, would involve universal adoption by lenders of a standard metric for evaluating the flood risk of individual properties. It would be more accurate than the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) flood maps that currently dictate insurance rates and purchase decisions.

This would help lenders to “provide various incentives and penalties to encourage prudent behavior by property owners … ” New mortgage products would encourage smarter property investment. And that would spur local governments, engineers and building materials manufacturers “to promote behaviors and capture new markets to reduce flood risk … ” according to Berman.

Yet another paper, authored by Johanna Bozuwa and Thomas Hanna, researchers at the Democracy Collaborative, offered more radical solutions. They’re broadly centered around the economic development strategy of “community wealth building.”

The paper calls for the promotion of mission-driven nonprofits (social enterprises) and worker-owned firms. These organizations “could prove to be transformative institutions in building more resilient infrastructure,” in part because they would enhance the political influence and economic stability of communities.

Likewise, expanding community-owned or controlled land and housing, such as through community land trusts, could also empower residents to defend against and bounce back from climate impact.

These projects and environmental initiatives could mobilize the resources and financial support of institutions with permanent stakes in their communities, including hospitals, universities and publicly owned businesses.