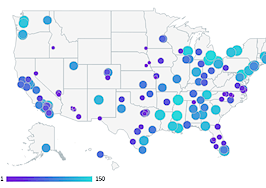

Affordability continues to be an issue across the U.S., especially in densely populated large metropolitan areas such as New York City, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle.

The majority of studies about affordability focus on numbers, percentages and ratios, but don’t particularly explore the real-life ramifications for those who are bearing the brunt of booming mortgage and rental prices.

Beyond the possibility of moving into a smaller home or apartment, an increasing number of people are priced out of housing altogether. That’s the focus of Zillow’s latest study, which found a correlation between rising rents and higher levels of homelessness in 25 of the largest metropolitan areas.

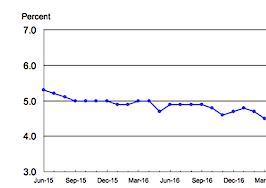

Between 2011 and 2016, homelessness rates in New York, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C. and Seattle increased by at least four percent and revealed a strong relationship between rising rents and growth in the homeless population. Philadelphia, Chicago, Minneapolis, Detroit and Pittsburgh also show a significant connection.

In New York City, there are currently an estimated 76,411 homeless people. Zillow data scientists projected that a five percent increase in rent would lead to an additional 2,982 people living on the street by 2018. In Los Angeles, there are currently an estimated 59,508 homeless people, and a 5 percent increase in rent would lead to an additional 1,993 people becoming homeless.

Currently, 11.1 million renters spend 50 percent of their monthly income on housing costs — well above the affordability benchmark of 30 percent or less.

In some cities, the overall cost of living is low, so renters have more room to allocate a greater portion of their monthly income to housing. But, in large metropolitan areas where the cost of living is incredibly high, renters have less flexibility in putting more money toward rent.

“We’ve seen so much pressure in rental housing markets that it’s created a rental affordability crisis that has spilled over into a homelessness crisis at lower income levels,” said Zillow Senior Economist Dr. Skylar Olsen in a press release.

“Often, the rental demand in these markets isn’t being met with a sufficient supply. There are several cities grappling with this problem, but there is no one-size-fits-all solution for everyone. This report puts a number on the link between rising rents and homelessness, highlighting the very real human impact that rent increases are having across the country.”

In the full study, five homelessness experts offered solutions on what can be done to help those who are currently dealing with homelessness and what can be done to keep additional individuals from living on the street or in shelters.

University of Pennsylvania Professor Dennis Culhane says the first step is to develop a more accurate way of measuring the current level of homelessness and a more accurate model for future projections. The current method depends on counting those in shelters and conducting one-night surveys for those who live on the streets.

According to Culhane, nearly 40 percent of the homeless population who live outside of shelters are missed during these one-night surveys, which results in an inaccurate allocation of resources from local and state agencies.

“Having watched some of these counting things up close, they concern me in terms of their reliability,” he said.

The next steps in the process include making it easier for people to receive housing vouchers, expanding the HUD federal budget for homelessness and crafting long-term game plans that address the root of homelessness, such as raising minimum wage to meet the cost of living, providing adequate drug and mental health counseling for those who need it, and a more robust construction of rental properties for lower-income communities.

“It’s a fundamental market failure we’re dealing with,” said Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab Program Director Tyler Jaeckel. “We have people working full time or more who can’t afford rent. There’s not enough decent and affordable housing, and we haven’t invested in that to the scale needed.

“It’s a problem of great enormity — and we have great programs on the margins to alleviate some of the conditions — but at the end of the day, you have to solve the market failure if you’re going to make headway on it,” he added.