Black homeowners in historically redlined neighborhoods have gained $212,000 less home equity over the past 40 years, according to a study released Thursday by Redfin.

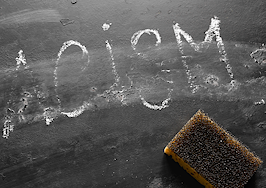

Redlining was formally and ostensibly outlawed in the 1960s, but the New Deal-era racist lending practice is still having a lasting impact on the rate of Black homeownership and Black wealth in the United States.

“More than half a century after it was abolished, redlining continues to dictate the racial makeup of neighborhoods and Black families still feel the socioeconomic effects of such a discriminatory housing policy,” Daryl Fairweather, Redfin’s chief economist, said in a statement.

“Black families who were unable to secure housing loans in the neighborhoods where they lived have missed out on one of the major ways to build wealth in this country,” Fairweather added. “And even families who were able to buy homes in their neighborhood after redlining ended haven’t earned nearly as much home equity as people who bought homes in neighborhoods that were considered more valuable.”

Redlining was the systemic practice of blocking services from certain communities — literally ones designated with a red line. The government-sanctioned practice — which was born when the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created as part of the New Deal during the Great Depression — assigned lower mortgage security ratings to Black neighborhoods, creating a significant barrier to obtaining loans.

It’s not uncommon for lending standards to tighten during times of economic turbulence, especially in the mortgage industry, but this practice specifically targeted Black communities and long-predated the Fair Housing Act by more than three decades.

In neighborhoods that were victimized by redlining, the typical homeowner has gained $196,050 in home equity since 1980, according to the study. The typical homeowners in greenlined neighborhoods, however, have gained $408,073 in home equity over that same time period.

The homeownership rate for Black Americans is still much lower in formerly greenlined neighborhoods. Since 1980, the homeownership rate for Black families in greenlined neighborhoods dropped from 50.4 percent to just 44 percent, while the rate for white families rose 4.1 percent to 71 percent in 2017, the year for which the most data was available.

Brittani Walker, a Redfin agent in Chicago, said redlining continues to contribute to segregation in her hometown.

“It’s a tale of two cities in Chicago,” Walker said. “It goes back to redlining, when Black residents lived in certain neighborhoods and white people lived in others, and the difference in home value and segregation between those places has been exacerbated by policy, education, wage inequality and so many other issues.”

Walker said she hears the systemic problems every day when she talks to clients — homebuyers will set certain boundaries from their own research or from friends.

“They don’t want to buy in certain neighborhoods, especially on the South Side in formerly redlined areas, because those places don’t get the culture, the restaurants, the fun events, they don’t even get healthy food at grocery stores,” Walker said. “And that contributes to why home prices don’t go up in those neighborhoods.”